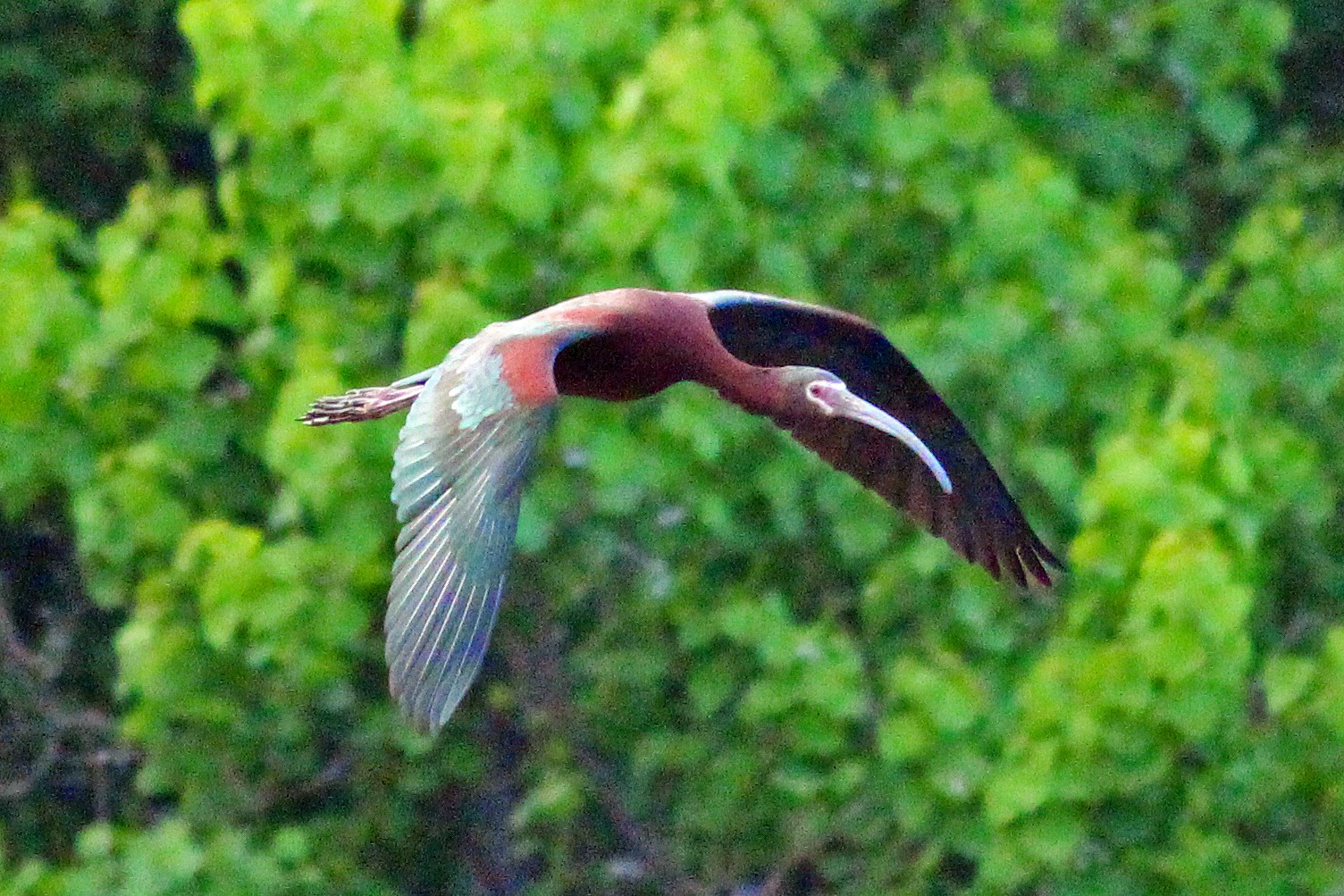

White Faced Ibis and Migrating Wading Birds at Joppa Preserve

|

| The Texas White Faced Ibis a State Threatened Species in Dallas, Texas May 23, 2014 |

Certain shorebird and wading bird species are the first push of migratory Central and South American birds through the Great Trinity Forest every year. They are only seen for a brief time as flock after flock stop to refuel for a day or even just an evening in the small ponds and wetland habitat along the Trinity River.

|

| White Faced Ibis silhouette in the fading sunset light May 23, 2014 |

The birds in many cases have flown the entirety across the Gulf of Mexico over water from the Yucatan to the mouth of Trinity Bay, non-stop. Others have flown across the Andes and the Sierra Madre working their way up the tidal pools and mud flats of the Pacific. Here they are, for a brief moment in time, in Dallas.

|

| Little Lemmon Lake full of shorebirds |

The drier than normal spring in 2014 has been harsh on many aquatic species and waterfowl. What is poor for some species is great for others. The mudflats of the half empty ponds and small lakes like Little Lemmon Lake in Joppa Preserve provide near perfect habitat for these birds.

|

| White-Faced Ibis in full breeding plumage Dallas, Texas May 23, 2014 |

Rare birds call this place a brief home, a roadstop motel of a place.

One such species, listed in Texas as a Threatened Species, the White Faced Ibis is a very rare sight to Texans.

The White-Faced Ibis is a long-legged wading bird with reddish eyes and a long, slender, decurved bill. Plumage is chestnut colored with green and purple iridescent. During the breeding season, a white feather border can be seen around the base of the bill along with red lores and legs. Juveniles lack the white on the face and the red legs.

To Dallasites the bird is very rarely if ever seen. A “life bird” for many who keep a checklist, seeing one in the wild would be a year’s highlight for many birding types.

The White-Faced Ibis is threatened due to habitat loss. It needs wetland areas exactly like those in the Great Trinity Forest to thrive.

The shallow wading pools in short grasses, flooded marsh and lowland areas are their prime habitat. Very few of these places still exist. It’s a real gem to have places like that here in Dallas.

Appreciated by few humans but adored by wildlife, the next year or two will tell the tale whether or not changes to the Trinity Forest will be impacted by construction plans.

American Avocet Recurvirostra americana

With its unique coloration, long legs and elegant profile, the American Avocet is striking among North American birds. The Avocet is a migratory shorebird that is characterized by a long, thin upcurved bill with distinctive black and white markings on its back and sides

The American Avocet or Recurvirostra americana is a long legged shorebird in the stilt family. It is considered a large shorebird at eighteen inches in length. The Avocet is charecterized by a long, thin bill that curves upward, more so in the female.

Year round it has a distinctive and signature black and white stripped pattern on its wings and back. During the breeding season the head and neck are a pinkish-tan. During the winter they turn more white.

American avocets prefer open water and marshy summer habitats such as lakes and ponds throughout the central plains of the United States, including the Rocky Mountain region and Canada.

During the winter avocets migrate to saltwater or brackish areas of the central and southern California coast, Baja California and the southeastern Atlantic coast as well as throughout Mexico and the Caribbean. Year round populations can be found along the South Texas coast and the southern California coast.

American Avocets forage while wading in shallow water by sweeping their curved bills back and forth along the surface of the water, or they can use their bills to probe into mud for insects or crustaceans. They may feed in flocks, and may dabble for food in deeper water.

Avocets are important members of their ecosystem; because of their food habits they likely have a regulatory influence on insect and crustacean populations, and they are an important food source for their predators. They also have an influence on the plants they eat as they often broadcast seeds into new areas.

Currently protected by the US Migratory Bird Act, American Avocets are making a comeback after over-hunting in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The main threats to American Avocets today are habitat loss and degredation.

Foraging With Migrating Shorebirds

|

| Wilson’s Phalarope in foreground and Lesser Yellowlegs in background |

|

| Plate by Alexander Wilson circa 1807 |

Often called the “Father of American Ornithology”, Alexander Wilson 1766-1813 was instrumental in the early scientific study of birds in what is now the Southern United States. His sketches and plates were some of the first that featured the American Avocet, Lesser Yellowlegs, Roseate Spoonbill and various small shorebirds.

A number of bird species now carry the “Wilson’s” name as an honor to the man who first studied them at length.

Wilson authored the nine-volume American Ornithology (1808–1814). Of the 268 species of birds illustrated there, 26 had not previously been described.

Lesser Yellowlegs Tringa flavipes

In winter, the Lesser Yellowlegs is found along the coasts of Mexico, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. The largest concentration of wintering birds occurs in Suriname and along the Gulf of Mexico.

Lesser Yellowlegs breed in interior Alaska and northern Canada. They breed between 51 and 69 degrees north latitude in suitable habitat. They breed farther north than their close relative, Greater Yellowlegs (Tringa melanoleuca), where they co-occur. Historically, some populations of Lesser Yellowlegs might have bred farther south then they do currently.

Wilson’s Phalarope Phalaropus tricolor

Wilson’s Phalaropes are a relatively small, long-legged shorebird. They are unique among Texas birds in that they are one of only a few species in which the female is much more brightly colored than the male.

The Wilson’s Phalarope can be distinguished from most other shorebirds by the bright coloration on their neck and head. Additionally, unlike other shorebirds, Wilson’s Phalaropes often feed while floating on the water, sometimes spinning like tops to stir up aquatic invertebrates.

The relatively long, thin bill, and bold blackish stripe on the neck and face distinguish the Wilson’s Phalarope from the red-necked phalarope (Phalaropus lobatus), which is a migrant in Texas.

In Texas, Wilson’s Phalaropes are most frequently found in wet prairie, flooded plains and other grass or sedge dominated wetlands. The presence of short vegetation in or adjacent to shallow pools of open water is an important microhabitat feature. Human-altered habitats, particularly flooded pastures and municipal wastewater treatment ponds, may also provide suitable habitat.

Because microhabitat conditions are very important to the Wilson’s Phalarope, water conditions greatly influence habitat use. The shallow wetlands on which this species depends are very sensitive to alteration, especially drainage and degradation resulting from human activities. When water levels are low, wetlands may be avoided due to the lack of standing water. Wetlands dominated by shrubs are also avoided by the Phalarope due to the increase risk of predators.

Artificial habitats, such as flooded agricultural fallow fields, may be utilized by Wilson’s Phalaropes because they provide necessary conditions lacking in native habitats.

|

| Wilson’s Phalarope with a worm in the recently flooded leaf detrius after a spring rain in 2014 |

Killdeer Charadrius vociferus

The killdeer is Texas most well-known member of the plover family, although many people know the killdeer without understanding its family affiliation. The killdeer can be common around human developments, frequently seen on playing fields, parking lots, and other unnatural habitats. Its “broken-wing” display is famous and known by many.

The killdeer often forms flocks after breeding in late summer. It feeds in fields and in a variety of wet areas, and in general, it is not prevalent on mudflats. It is noisy! Breeding residents to North Texas they are a common site.

Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius

Spotted Sandpipers are the most widespread sandpipers in the United States, having colonized their broad breeding and winter ranges by using almost all habitats near water. These include the shorelines of large rivers and lakes to urban and farm ponds.

Spotted Sandpipers (Actitis macularius) are found throughout North and Central America, including the western Caribbean islands. Their breeding range extends from the northern Arctic to the southern United States. Their wintering grounds range from the extreme southern United States to southern South America, along with all the Caribbean islands. Spotted Sandpipers live year-round along the western coast of the United States and in parts of California.

The Spotted Sandpiper is a common migrant throughout the Lone Star State from late March to early May. The fall migration period extends from early July to mid-October. Absent in the hottest of summer months, they are quite common in the Great Trinity Forest ponds in the late summer and early fall.

These sandpipers are winter residents in Texas with abundance varying from common to rare depending on latitude and climate.