Scissor-tailed Flycatchers and Kingbirds In Texas Trinity River Corridor

|

| Texas Bird of Paradise, the Scissor Tailed Flycatcher perched on an Arkansas Yucca surrounded by Prairie Coneflower and other native wildflowers in Dallas, Texas |

The strong southerly winds of a Texas spring bring more than humidity up from the Gulf of Mexico. Riding the air currents north from as far away as the tropical rainforests of Central and South America are the flycatchers of the bird world.

|

| The dripping wet blossoms of an native Arkansas Yucca just after an spring thunderstorm at McCommas Bluff Preserve, Dallas Texas, Spring 2014 |

|

| Scissor-tailed Flycatcher at the Mockingbird-Westmoreland Bridge in the Trinity River Floodway, Dallas, Texas. Downtown Dallas and Victory Park can be seen in the distance |

The flycatchers are fond of the open spaces and fence lines of the Trinity River. In the late Spring, June to be precise, the birds move into Dallas in great numbers setting up shop among high insect populations that dominate the fields here. The three most dominant species seen are the Scissor-Tailed Flycatcher, the Eastern Kingbird and Western Kingbird. The Trinity River Corridor serves as a great overlap for the Kingbird species with near equal amounts of both Eastern and Western species.

Scissor-Tailed Flycatcher Tyrannus forficatus

The Scissor-Tailed Flycatcher Tyrannus forficatus is known by other names as well… Scissortail, Texas Bird-of-Paradise and Swallow-Tailed Flycatcher.

From the appearance, it is obvious how the bird acquired its common names, but its former Latin name – Muscivora forficata, describes the bird in even grander terms. Muscivora derives from the Latin word for “fly” (musca) and “to devour” (vorare), while Forficata comes from forfex, or scissors. The scissortail now is a member of the genus Tyrannus, or “tyrant-like flycatchers.”

Strong willed and fearless, the best comparison one can make to such a bird is the familiar Mockingbird who also readily defends territory, nest sites and has a qualification for fighting dirty.

|

| Scissor-Tailed Flycatcher perched high above an endless meadow of coneflowers near Piedmont Ridge Trail in the Great Trinity Forest |

Scissor-Tailed Flycatchers hunt by sight and by ambush. Many see Scissortails lining barbed wire fences, telephone lines or even road signs. Those artificial perches afford great over watch of a field.

The photos here were taken entirely in wildscape. Meadows, fields and treelines along the Trinity River and in East/Southeast Dallas along lower White Rock Creek in an area called the Great Trinity Forest.

So many know White Rock Creek as it moves through North Dallas but so few ever see it beyond the outfall of the White Rock Lake Spillway where the creek slows, the trees get larger and the scenery much more photogenic.

|

| A good look at a departing Texas Bird of Paradise, the Scissor-Tailed Flycatcher in full breeding plumage |

Scissor-Tailed Flycatcher Attack Sequence On a Red-Tailed Hawk

|

| Scissor-Tailed Flycatcher moves in on a trespassing Red Tailed Hawk |

In some areas like the Trinity River Floodway, perches and tree cover for nesting sites are scarce. This is an area between the levees near the Industrial District and Downtown where lone Cottonwood and Pecan trees dot the landscape. They are the usual haunts of resident Red Tailed Hawks year round. When flycatchers come in to nest, there will be many nests in one tree as habitat is a premium. That leads to conflict and dramatic attacks result.

Red Tailed Hawks will actually prey on nests of other species. Documented cases of nestlings being eaten by hawks are well known. The Scissortail goes the extra mile to make a point with the Red Tailed Hawk in this photo, delivering what appears to be a quite painful strike to the back of the hawk’s neck.

|

| Contact with the hawk, the Scissortail is riding the hawk like a winged horse |

|

| The hawk screams in pain and maybe disbelief as the plucky Scissortail unleashes an aerial assault. Note the long Scissortail on the back of the hawk |

|

| Splash one hawk. The Scissortail returns to his nest. |

This genus earned its name because several species are extremely aggressive on their breeding territories, where they will attack larger birds such as crows, hawks and even owls. Beautiful and ounce for ounce some of the heaviest hitters among Texas birds.

|

| Rarely documented mirroring mating dance behavior of Scissor-tailed Flycatchers |

Scissor-tailed flycatchers are easily identified by their long, scissor-like tail, which may reach nine inches in length. During flight, the bird opens and shuts its taillike a pair of scissors and folds or closes the “scissors” when perching. Since the bird is only 12 inches long, its tail is proportionately longer than any other Texas bird including Roadrunners.

|

| The signature call of the Scissortail |

Scissor-tailed flycatchers are considered Neotropical migrants birds that spend their winters in Central and South America, returning to North America to nest and raise young.

As a rule, scissortails are seen in Texas from early April to late October, though individuals occasionally are seen during the last week of March and some birds linger until mid-November.

Most likely their residency in Texas is tied to the first killing frosts of the Fall, which diminishes food supplies for the birds.

The scissortail is one of the earliest summer birds to arrive each spring. Across most of the Trinity River Corridor, Dallasites can begin looking for them during the first week in April. Their limited nesting range is primarily concentrated in the southern Great Plains states, from New Mexico to Louisiana and Nebraska southward to southern Texas and adjoining areas of Northern Mexico. However, the birds have wandered and documented as far north as Hudson Bay in Canada.

|

| The brilliant colors of a Scissortail in near perfect light of a Texas sunset |

The nape of the scissortail’s neck and back are pearl gray, and the breast is white. Wings are smoke coal black with a touch of crimson at the shoulders while the sides and wing linings are pink. Females usually are shorter than males because her tail is not as long.

|

| Breeding pair of Scissortail Flycatchers riding the stiff wind currents on the evening of June 16, 2014 |

|

| A Scissortail bounds of the perch of a yucca to attack an unsuspecting insect below |

|

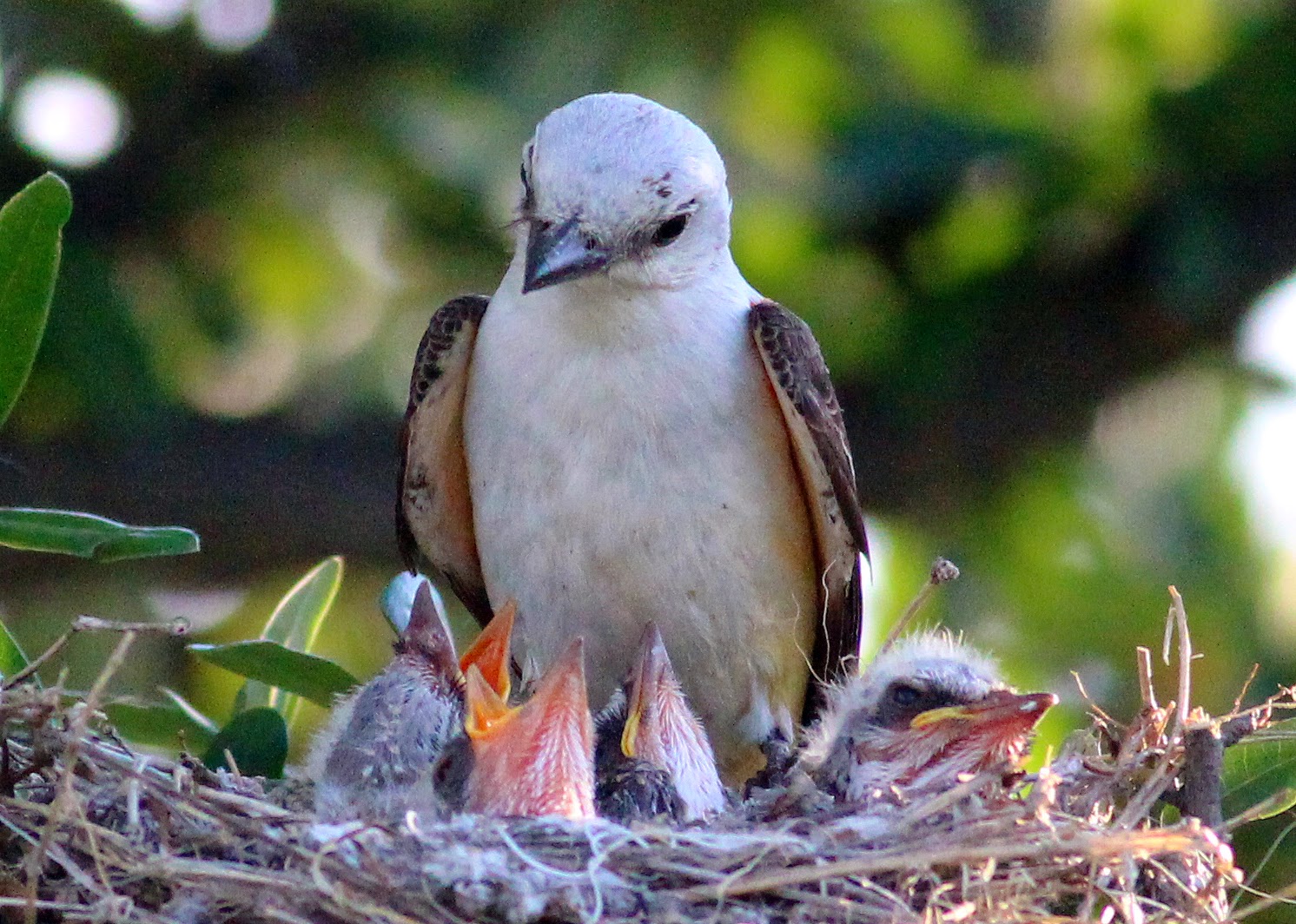

| Scissor-Tailed Flycatcher nest with four nestlings, June 13, 2014 |

The nesting habits for the Scissor-tailed Flycatcher include a small diamter stick nest lined with soft fiber material in an isolated tree where three to five eggs are laid. The female builds the nest and the male often adds the fiber material during the building process.

|

| A Walking Stick becomes dinner for a Scissor-tailed Flycatcher nestling |

Both parents work all day long to feed the nestlings. Moths, butterflies, June Bugs, grasshoppers and even Walking Sticks are standard table fare at these nests. 2014 seems to be a particularly banner year for these insects. Walking Sticks consume the foliage of oaks and other hardwoods. Severe outbreaks of the walking stick, Diapheromera femorata, have been documented in the Ouachita Mountains of Arkansas and Oklahoma. The insects eat the entire leaf blade. In the event of heavy outbreaks, entire stands of trees can be completely ravaged. Continuous defoliation over several years often results in the death of the tree. Birds like flycatchers help control the population of these insects.

|

| Adult flycatcher removing waste from the nest site |

Arkansas Yucca Yucca arkansana— Photogenic Perch For Flycatchers

|

| Native Yucca in the brilliant sunset light growing on the bluff tops of the Trinity Forest |

As a rule we think of Yucca as desert fare, but it is a common Texas plant often seen in undisturbed areas along the bluff tops of the Trinity River and White Rock Escarpment running through the Great Trinity Forest.

One of the smallest yucca in Texas, Arkansas Yucca ranges from South Central to North Central Texas, into Oklahoma and Arkansas, preferring chalky pan soil on rocky hillsides and prairies. It has asymmetrical rosettes in small open groups.

Like most yucca, the leaves are bluish-green to yellowish-green with white margins and curly threads on the margin.

As is, the “stem” of the yucca looks woody (it has to be strong to support that mass of blooms.) Dead yucca leave a strong supporting “stick” for lack of a better term. These particular groupings stand tall above the wildflowers, from 3 to 4 feet standard.

There are over two dozen US species of these plants, much more widely distributed than agave, ranging across the Midwest, Great Plains and all the eastern states in addition to the south, in mixed environments including deserts, grassland, mountains and coastal scrub.

Yucca also extend through Mexico towards Central America. All species have the capability to grow tall and branch, though in some arid locations this does not happen, and the plants remain compact and single. Flowers are white and bell-shaped, growing in a great mass on a shortish stalk; they are usually produced once a year though may not appear if weather conditions are unfavorable.

Eastern Kingbird Tyrannus tyrannus

|

| Eastern Kingbird Tyrannus tyrannus as seen hunting for insects among a grouping of wild Prairie Coneflower along a limestone escarpment along Lower White Rock Creek, Dallas Texas, 2014 |

The dressed to kill flycatcher of the Great Trinity Forest accolades go to that of the Eastern Kingbird Tyrannus tyrannus. A bird dressed in a tuxedo with fine lines and a descriptive ability to crush any and all insects that venture near.

The dressed to kill flycatcher of the Great Trinity Forest accolades go to that of the Eastern Kingbird Tyrannus tyrannus. A bird dressed in a tuxedo with fine lines and a descriptive ability to crush any and all insects that venture near.

The kingbird is easy to identify from other flycatchers with its contrasting black back and white chest, giving it the appearance of wearing formal dinner attire. The black tail is tipped in white, making it easily recognizable.

Black and white is not really the norm for flycatchers and songbirds. The Eastern Kingbird is unique in this way. Reds and yellows are more common. But for what he lacks in color and song, he compensates for nicely in presentation and style.

|

| An Eastern Kingbird weighs down an already blossom laden and top heavy Arkansas Yucca |

Eastern kingbirds are flycatchers, which is considered the largest family of birds on Earth, with over 400 species. The Eastern Kingbird exhibits that classic flycatcher silhouette, complete with the slight crown or ruffled head that is common among other flycatchers such as phoebes, wood pewees and so on.

|

| Caught in mid air, an Eastern Kingbird hovers like a hawk in an effective technique to spook insects out of a hiding spot |

Eastern Kingbirds also exhibit typical flycatcher behavior, called sallying, where they fly out from a perch in pursuit of flying insects, and then often returning back to the same perch (also called hawking).

They feed mainly on insects during breeding season, but oddly enough, during migration and on their wintering grounds in South America, kingbirds change personalities and behave almost docile, flying around in flocks, feeding on mainly fruit.

|

| While as large as a Mockingbird and with similar colors, the Eastern Kingbird has a more robust and stockier build |

Western Kingbird Tyrannus verticalis

|

| Western Kingbird Tyrannus verticalis |

One of the most common birds to spot in the Great Trinity Forest in spring are the hearty Western Kingbirds Tyrannus verticalis. From prairie areas of the Lower Chain of Wetlands to the deep swamps of Rochester Parks, these birds are visible at every turn from dawn to dusk.

Before the pioneer settlement of the Southern Plains the Western Kingbird range undoubtedly was restricted by the lack of advantageous perches in otherwise prime open country habitat. Its range in Texas in the early 1900s was the western part of the state encompassing the Panhandle, southern plains, and the mountains west and south of the Pecos River Valley.

Since the early 20th century, man’s opening of woodlands for timber harvest/farming, planting of trees on the plains, and construction of power lines, and other structures which accompanied settlement have facilitated expansion of Western Kingbird breeding range.

Nesting had spread by the mid 20th century east to Austin and by the late 1960s to the upper Texas coast. By the early 1970s they were nesting in the Dallas Fort Worth area.

Western Kingbirds migrate from Central America to breed across the western United States during the spring and summer months–about April through the end of August/early September.

They leave their breeding grounds relatively early and are generally not seen in the western states from about mid-September through early May. They tend to be viewed around farms, meadows, and along fence rows near dry open fields with scattered trees and brush.

Western Kingbirds are members of the flycatcher family and are often seen hunting insects from fences and small bushes and trees along roadsides. They are about 9 inches long with a wingspan of about 16 inches. They have gray heads and chests, thick dark bills, yellow bellies, and dark tails with white edges. They can be aggressive and often harass large raptors

|

| Western Kingbirds on guard |

Just like Scissortailed Flycatchers, the Western Kingbird readily defends nest sites, habitat and favored trees from any predator or competing bird species. The telltale flash of yellow as the beat through the high grass is an easy way to spot these birds which very much resemble the Eastern Kingbirds, a distant cousin.