President Sam Houston’s Camp On White Rock Creek, Great Trinity Forest

|

| President Sam Houston circa 1840s |

During his final term as President of the Texas Republic, Sam Houston’s chief concerns were Indian relations, war clouds on the horizon with Mexico and Texas annexation into the United States. Sam Houston, who had lived with the Cherokees for years as a young man, had a fondness for the tribes and wanted them treated fairly as their lands were taken over by civilization despite their depredations against the settlers in Texas.

|

| White Rock Spring in July, site of Sam Houston’s Camp |

|

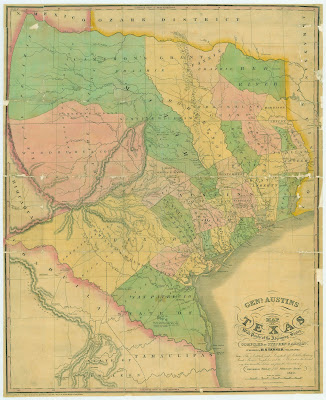

| Map of Texas 1840 |

It was in July 1843 when Sam Houston and an expedition of about 30 men departed Crockett in East Texas, and began their trek to the Three Forks of the Trinity to negotiate with the chiefs of the Indian tribes. Their route was well documented traveling roughly on the same route into Dallas that US Highway 175 takes today. This route was an ancient Pre-Columbian trail used by Indians for many centuries as an imporant trade route between the Piney Woods of East Texas, the Plains and Indians living north of the Red River. Scyene and Preston Roads share similar distinctions in Dallas as ancient Indian trails that later became major roads.

|

| Looking south with White Rock Spring in the far treeline beyond at the base of Pemberton Hill |

A man who was traveling with Houston, an Englishman named Edward Parkinson wrote an account of Houston’s journey, mentioning sites of note, and a typescript of his diary is in the collections of the Dallas Historical Society. Other notable members of the entourage included future cabinet members of President Jefferson Davis in the Confederacy, future Civil War generals, Indian Fighters, judges and few rascals thrown in for good measure.

Parkinson described in his diary the difficulties and trials encountered by the expedition. The men had to literally hack their way through groves of Bois d’arc trees in the Trinity River bottoms east of present day Dallas before crossing the river, were overtaken by hordes of insects and killed buffalo to sustain themselves. President Sam Houston and his men met with John Neely Bryan on July 14th in what is present day Downtown Dallas near the Old Red Courthouse as they were passing through to Bird’s Fort. A couple men from the group were taken with fever and stayed behind at White Rock Spring unable to continue on. White Rock Spring was a great place to stay behind since Dallas at the time was largely a barren plain with little shade in the heat of the summer. They stayed in the company of John Beeman and his family who were the first family to settle in Dallas.

|

| Looking north from White Rock Spring |

John Beeman chose the White Rock Spring area off present day Pemberton Hill Rd to settle. John Beeman migrated to the Peters Colony which was part of Nacogdoches County at the time. On April 8, 1842 John Beeman, brought his family to White Rock Creek; building his cabin and planting the first corn in Dallas County. He initially built a fortified “blockhouse” a two story prairie defensive tower house just south of present day Military Parkway. He later moved to the Pemberton Hill area the next year. After annexation John Beeman was elected the first US Congressman to represent North Texas.

|

|

| View of Pemberton Hill looking east from White Rock Spring |

The photo above shows a grove of walnut and pecan trees directly north of White Rock Spring. The single walnut tree just to the left of the road has seen quite a bit of history. The story is that the tree has two spikes driven in it on the trunk. One to note the high water mark of the great 1908 flood that destroyed much of Dallas. A second spike, even higher, noting the high water mark of the 1866 Trinity River flood.

|

| Honey Bee hive inside the walnut tree with the spikes driven in it |

|

| Large Alligator Snapping Turtle in White Rock Spring |

When Houston arrived at Ft. Bird, several tribes had shown up but did not want to go near the garrisoned fort fearing a trap. Houston moved the negotiations and camps six miles north to Grapevine Springs. He felt the Springs offered better water, more shade in the summer heat and less mosquitoes. However the group camped there for more than a month while awaiting the Comanches, and was described by Parkinson as: “there were some fine though rather monotonous days, only relieved by finding a bee tree or killing our beeves.”

At this time, along with the negotiations with the Indians, Houston was still President of the Republic and having to deal with the Mexican situation and annexation of Texas. Before the actual treaty was signed, he had to go back to Washington on the Brazos to deal with these issues personally. To deal with the Comanches when, and if, they arrived he assigned Gen. Edward H. Tarrant and Gen. George Whitfield Terrell. The treaty was signed in the last three days of September 1843.

The Treaty at Birds Fort was a rare instrument: it was actually ratified by the Republic of Texas Senate. Throughout both his administrations, Sam Houston worked to negotiate with the Texas tribes, not only because of his natural inclination but also because the new Republic simply could not afford to be at war both with the Indians and the Mexicans. His policy had already been put into practice when he and John Forbes negotiated a treaty with the Cherokee on February 3, 1836.

Below is the last page of the Bird’s Fort Treaty

Bird’s Fort Treaty Ratification Proclamation, 1843

That I, Sam Houston, President

of the Republic of Texas, having seen

and considered said Treaty, do, in

pursuance of the advice and consent

of the Senate, as expressed by their res-

olution of the thirty first of January,

one thousand eight hundred and forty

four, accept, ratify and confirm the

same, and every clause and article

thereof

In testimony whereof, I have

hereunto set my hand and caused

the Great Seal of the Republic to be af-

=fixed

Washington, this

third day of Feb-

=ruary in the year

of our Lord one thou-

=sand eight hundred and

forty four and of the

Independence of the

Republic the Eighth.

By the President

Sam Houston

Anson Jones

Secretary of State