Reveau Bassett, Frank Reaugh and the Great Trinity Forest

|

Accounts of Frank Reaugh and Reveau Bassett’s lives limited to their work as pioneer Texas artists would, by itself, make a rich and interesting story. But there was much more to these extraordinary men. In rustic, down to earth ways they shared some of the same characteristics of Mark Twain and Leonardo da Vinci. Besides being painters they were amateur naturalists, photographers, philosophers, noted public speakers and in the case of Reaugh, an inventor. The depth of their work extends deep into the heart of Texas. They painted dramatic Texas landscapes, livestock, wildlife and waterfowl to form a deep connection with the part of Texas they called home. Prolific artists, they created thousands and thousands of pieces. While a number of their works include canvases depicting the Sangre de Cristos of New Mexico or the Llano Estacado of West Texas, a large number of their pieces come right from their own backyard. The Trinity River.

The consumers of their work included some of the most well known families and art collectors in Dallas. The Murchison’s, the Starke Taylor’s, the Woodall Rodgers’ of a growing Dallas. I think those early collectors were drawn into the artwork because of the way the artists captured the essence of the places that were put to paint. Many of these collectors were originally from East Texas like the Murchisons and were familiar with the realistic nature of many pieces painted by Bassett and Reaugh. These private collections formed the backbone of the original Dallas Museum of Art. Many pieces can still be seen there today. Their works were integral pieces of the Mural Room at the Baker Hotel, Highland Park Village Theatre, The Petroleum Club, Fair Park and galleries all over the country.

One underlying drive behind their painting was to capture scenes they felt would not exist in the future. Ones they wanted to put down for history since that way of life, that environment would be sure to soon disappear. For Reaugh, it was a barbed wired prairie that he felt spelled the end of his genre. For Bassett, it was a bulldozed river bottom he feared most.

In some ways they were right. Some can say we have reached a tipping point, back from the brink, where things are starting to head in the right direction. In some regards to their past work in the Great Trinity Forest, the scenes they painted 75-100 years ago are a carbon copy of what can be seen today.

|

| Reveau Bassett Mallards |

|

| Ned Fritz with the secret Saw Palmetto Palm Trees |

Until recently, I had no idea Reaugh, Bassett and others like Olin Travis had spent so much time on the river. It was not until one of their pupils contacted me about Lemmon Lake. She was a student of Frank Reaugh in the 1930s and they would often take field trips around Dallas to sketch and paint. Lemmon Lake was a favorite spot at the time, given the diversity of plants, wildlife and landscape. She had not been to the lake in over 70 years but was able to describe the sights, sounds and smells as if she was there just yesterday.

I had always thought pioneering attorney Ned Fritz was probably the original. He is the man who deserves all the credit for saving what we have left of the Trinity and was a champion at saving the Texas Buckeye Grove at William Blair Park in Dallas. He made his lasting mark on the Trinity with his efforts to keep the government from channelizing the Trinity from Dallas to the Gulf of Mexico in 1973. What he saw back then was a patchwork collection of old remnants of Trinity River bottomland when roughly cobbled together formed one of the largest urban parkland areas in the United States. In theory only. It was not a reality until much later with bond funds slowly purchasing land, parcel by parcel. Even today, that process is ongoing. For better or worse.

I think a lot of folks want to nail down an event horizon or birth date in the present, when the Great Trinity Forest became a reality. 1994. 1998. 2005. Maybe the opening of the Audubon Center. Or the Buckeye Trail. Truth is, the woods have always been there. The places, the people, the wildlife. None of it ever left. Look at what was there 100 years ago through the brush strokes of Bassett and Reaugh to see not much has changed.

|

| Reveau Bassett Lemmon Lake |

|

| Lemmon Lake 2012 |

|

| Frank Reaugh (center) and Reveau Bassett (far right) on a sketching trip |

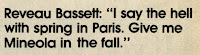

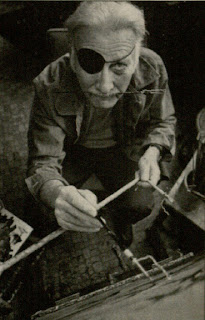

Reveau Mott Bassett 1897-1981

A Native Texan, Reveau Bassett came naturally into his chosen field of art. His father was chief engineer for Dallas Waterworks and originally moved to Texas in conjunction with the construction of the Texas Pacific Railroad. The Dallas Waterworks Corporation was the original water service provider for Dallas until it was purchased by the city and became Dallas Water Utilities. It operated water supply service to the city in the late 1800’s. First supplying water from the Trinity River, then from Browder Springs near present day Old City Park. As chief engineer his father was responsible for insuring a reliable water supply. As the city grew so did his responsibility. Eventually overseeing construction of city reservoirs on Turtle Creek and at Record Crossing.

As a youth, Reveau Bassett hunted and trapped along the Trinity River with his father, studying and sketching the birds and animals as they migrated through the territory. At the age of 12, he became a student of Frank Reaugh. Later joining him on sketching trips across the country. Like many famous Texas impressionists, from Reaugh he learned the refined art of drawing and painting. He studied at the National Academy of Design and also at the Art Students League where he was taught by William Robinson Leigh. Bassett quickly became widely known for his paintings of ducks and other migratory birds.

At its June 1936 dedication, former Gov. Pat Neff called the Hall of State “The Westminster Abbey of the Western World.” In the great chamber of the Hall of State, Eugene Savage, a New York artist, assisted by Reveau Bassett and James Buchanan Winn painted scenes depicting Texas history. These murals are 80×30 feet in a modified Byzantine style.

The Dioramas and views of Dallas County

Some of the more interesting Bassett works are not paintings at all. They are the famous diorama scenes at Fair Park in the Museum of Nature and Science. Fifty in all, spread out over four galleries, the dioramas portray native Texas wildlife in their natural settings. A couple years ago at the State Fair, I went through the old halls. The dusty old Roseate Spoonbill scene caught my eye. Looking at it, I could have sworn it was Lemmon Lake. The trees, horizon, clouds, it was perfect. Reaugh’s former student told me she was told Lemmon Lake was the setting for the diorama at Fair Park. Such a long forgotten lake that ended up being a focal point of so much of Bassett’s work.

The real scene from 75 years later at Lemmon Lake above of a near identical Roseate Spoonbill is one where you realize how much of a master Reveau Bassett was at color and light. Stood the test of time. The dioramas are looking a little ratty these days. Since the dioramas are now historical art, generous foundations have stepped forward to preserve them. The Hoblitzelle Foundation, The Harry S. Moss Foundation, The Constantin Foundation and The Charles E. Goddard Foundation. It’s a great investment in preserving a piece of the past, for the future.

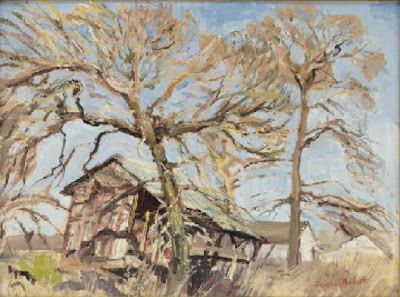

Reveau Bassett also painted old cabins in Dallas County. The one in the painting below, bracketed by two large trees looks near identical to the old abandoned Japanese Truck Farm shacks at Joppa Preserve.

|

| Reveau Bassett The Old Shack |

The resemblance is uncanny, although the “real” shacks have been reduced in size by gravity of late.

In April 1977, Ellen Stone interviewed Reveau Bassett for an article in D Magazine. The great article worth a read is below at the link:

D Magazine The Artist As Sportsmanhttp://www.dmagazine.com/Home/1977/04/01/Profiles_THE_ARTIST_AS_SPORTSMAN.aspx?p=1

One notable quote from the article is Bassett’s resignation about losing the landscapes he so loved to paint “There’s nothing around here now. Bulldozers have gotten everything. There’s concrete everywhere.” The 1970s were a dark time for the Trinity River. Widespread gravel operations, new landfills and new housing developments encroached on the land he knew so well. He passed away in 1981, a time when the Trinity River’s existence was frail.

The Leonardo of Longhorns, Frank Reaugh 1860-1945

Frank Reaugh born on the eve of the Civil War in Illinois just a month after Lincoln took office. His father had gone overland to California eleven years earlier as part of the original ’49er gold rush seeking a fortune he never found. He eventually returned to Illinois, marrying and having one child, Franklin Reaugh. In 1875, they loaded up a covered wagon and moved to Texas seeking a new life in the Southwest. Frank Reaugh was 15 at the time and pencil sketched their trip through Missouri, Arkansas and East Texas before settling southeast of Dallas near Terrell. At the time, their farm had the only fence as far as the eye could see. In his words it was the “open range, wild and free”. It was during those early days that Reaugh began his studies of cattle. Subjects were all around him, a living part of the natural environment of free, rich green pasture.

Reaugh, on his own or without knowledge of the impressionist movement in Europe became his own self taught plein air painter. Many of the French impressionists at the time were doing similar work painting out-of-doors. He was doing the same among the open prairies and bottoms of North Texas. For Reaugh, it was always about the animals and subtle light in the scenes, not the cowboys and wild scenes that his contemporaries Charles Russell and Frederick Remington enjoyed as subjects.

Reaugh, on his own or without knowledge of the impressionist movement in Europe became his own self taught plein air painter. Many of the French impressionists at the time were doing similar work painting out-of-doors. He was doing the same among the open prairies and bottoms of North Texas. For Reaugh, it was always about the animals and subtle light in the scenes, not the cowboys and wild scenes that his contemporaries Charles Russell and Frederick Remington enjoyed as subjects.

Reaugh’s formal education in art began in 1884 with classes at the Saint Louis School of Art. After a few months he returned to North Texas and began painting a prolific amount. Slowly but surely he began to develop into an artist that could sell his works and by 1888 he had saved enough money to sail to Antwerp. For a short time he studied at the Julien School of Art in Paris, where he finally became aware of the works of French impressionists. Ones with similar styles to his own works. It was on this trip that Reaugh studied under the Dutch landscape painter Anton Mauve. Just six years before Reaugh was taken under Mauve’s wing, Vincent Van Gogh studied with Mauve in the same town and in the same manner.

|

| Reaugh House 8th and Beckley Oak Cliff, Texas |

In 1890, the Reaugh family moved from Terrell to Oak Cliff. They built a home at 110 East Eight Street where the Adamson High School softball field stands today. At the back of the house his father built a separate place, a studio workshop and living quarters. The frame of the building was galvanized metal and quickly earned the nickname “Old Ironsides”. Above the building was a lookout type loft which served as Reaugh’s living quarters.

|

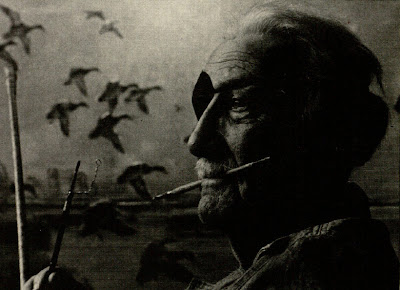

| Reaugh field trip to Trinity River, Dallas Texas 1906 |

The move to Dallas was a good one for Reaugh. Being close to town afforded his artwork more exposure. He spent a generous part of his career as a teacher. First on an informal basis then as director of the Dallas School of Fine Arts. Along with teaching, Reaugh organized field trips studying and sketching directly from nature. Some of field trips even went far beyond North Texas and lasted a month or more.

|

| Hale Bolton and Frank Reaugh sketching Clear Fork of the Brazos Palo Pinto County 1916 |

By the late teens and early 1920s he had cemented himself as Dallas own art guru, expanding his instructional classes and excursions deep into the Southwest.

The means of transportation used is an interesting conversation on the change of times and the character of Reaugh. Oxen pulled a wagon for the first trip. Mules pulled wagons later. A buggy and a Studebaker were used for later trips. From 1916 to 1941 a Ford of some flavor was used. These were always older models to which pet names were often given.

El Sibil

In 1928, Frank Reaugh commissioned a new studio for his work, El Sibil “The Vault”. Located at 122 E. 5th Street in Dallas, the location served as a studio, gallery, school and residence for Reaugh. It still stands today.

Inspired by Mediterranean architecture, El Sibil was largely Reaugh’s own design. James Cheek was the principle architect turning Reaugh’s design into reality. It incorporated many features of the “Old Ironsides” studio. Lots of indirect natural light, southern exposure, vaulted ceilings and an elevated sleeping area.

Inspired by Mediterranean architecture, El Sibil was largely Reaugh’s own design. James Cheek was the principle architect turning Reaugh’s design into reality. It incorporated many features of the “Old Ironsides” studio. Lots of indirect natural light, southern exposure, vaulted ceilings and an elevated sleeping area.

It was here at El Sibil where Reaugh taught more than art. On nature hikes around Dallas he would inform his students of the plants, animals and sky around them.

A sketch from nature should be a truthful record of things seen, and free from anything else. It should be a definite time and place and a reliable work of reference. It should not be retouched or changed in any way after it leaves the place of making… Nature’s beauty of design is matchless.

Much like Reveau Bassett, Reaugh had reservations on the future of the woods, prairies and wilderness he documented in his works. In his 1940 last will and testament he wrote:

“The main part of my property is in pictures. These are largely of the great prairies of Texas and the long horned cattle of fifty years ago, it is my intention to present this collection to the Southwest… It is my wish that these pictures be kept together if only for historical reasons. They create the spirit of the time. they show the sky unsullied by smoke, and the broad opalescent prairies not disfigured by wire fences or other signs of man.”

Today, Reaugh’s paintings are located in private collections throughout the Southwest, and in public institutions as dictated by his 1940 will. His legacy lives on in the work of the Dallas Nine, the Dallas Museum of Art and schools throughout the state who keep his paintings on permanent display.

Funny that the same weekend I had a woman contact me about Lemmon Lake, I would come across a couple of loose longhorns in far southeast Dallas on Pemberton Hill. The grass is always greener on the other side of the fence and these two decided on a late afternoon clover snack. In the background are a Dallas Police and Dallas Sheriff squad cars. I was secretly hoping to see the police tangle with a lassoed longhorn but it was not to be. A little gentle coaxing got them back off the road and home.

It’s easy to find spoonbills and ducks to show how little the Trinity River has changed in the last 100 years. I was scratching my head thinking, man, where in the world can I find free ranging longhorns in Dallas. Well, here they are.

|

| Bulls On Parade loose longhorns on Pemberton Hill Road January 2012 |

I can’t help but think of how much intestinal fortitude it must have taken for Reaugh to sit painting among a half wild herd of these large animals. Reaugh wrote that he was still enough, for long enough that a inquisitive longhorn would often openly challenge him in a field, thinking he was not human.

|

| White-Faced Ibis January 2012 |

I have often thought that one of the exciting draws to the Trinity River is that the environment there is tougher and harder than you are. It can take a monumental beating and bounce right back. Take for instance the bird in photos to the left and below. That is a White Faced Ibis (Plegadis chihi) at the Wetland Cells near Joppa. Rare to see an Ibis in January, in the dead of winter. The bird itself is a Threatened Species here in Texas, making it a rare sight any time of year. Seeing things like this makes you realize maybe the Trinity is not as ruined as one imagines.

I think for many North Texans, the treasure of the Trinity River eludes them. The Trinity is often the butt of many jokes and is often cast in a less than favorable light when pollution problems make headlines. The truth is the wild river that Reaugh and Bassett knew, never left. Their scenes that now command $20,000 in art auctions can be seen in the flesh. It’s still there. Despite all the headwinds, it survives.

|

| Twilight over the Trinity River Wetland Cells January 2012 |

|

| Wood Stork over the Trinity River July 2011 Dallas Texas |