Natural Springs In Dallas — Radiocarbon Dating One Of Texas Last Surviving Natural Springs

One of the few natural springs left in Texas and one of just a handful on public property, Big Spring is quickly becoming a focal point of intense study in the Great Trinity Forest. So much is yet to be learned about this natural spring that for every question and answer, another ten questions are spawned. The random guessing and hypothetical discussion of such a place has lately turned into a search for hard facts, scientific discovery and a determined goal for perpetual preservation.

|

| Looking down into Big Spring |

The unknowns of the place still vastly outweigh the knowns. How old is the spring, how old is the water, who lived here, who visited here, what’s under the ground, how was the spring formed. Slowly some of those questions are being answered. It will likely take years to fully understand the place.

The search for answers is a fun project. With an average flow of 23 gallons per minute year round and water pure enough to drink, the Spring is a great outdoor classroom for not just children but adults too. Classified as a Magnitude Five natural spring, delivering over 8 million gallons of clean water annually to the Trinity River watershed it might be one of the cleanest if not the cleanest source of water on the whole of the 710 miles of Trinity River. For certain the cleanest water in the watershed in Dallas County. Bar none. If there is cleaner water, I cannot find it.

The search for answers is a fun project. With an average flow of 23 gallons per minute year round and water pure enough to drink, the Spring is a great outdoor classroom for not just children but adults too. Classified as a Magnitude Five natural spring, delivering over 8 million gallons of clean water annually to the Trinity River watershed it might be one of the cleanest if not the cleanest source of water on the whole of the 710 miles of Trinity River. For certain the cleanest water in the watershed in Dallas County. Bar none. If there is cleaner water, I cannot find it.

Radiocarbon Dating Big Spring’s Water To the 14th Century

In addition to monthly water monitoring, one of the most unique tests conducted recently was a radiocarbon dating test of the water at Big Spring. The $600 cost for the test was paid for by fourteen citizens interested in the preservation cause. Conducted in late August 2013, the water test was sent to Beta Analytic in Florida for analysis.

|

| Small pipe placed deep into one of the spring’s outlets for the test |

The results took the balance of a month to get back and show the water being dated to 1360 AD. When dealing with variables like water, many things factor into the age of the sample taken. The soils and rock it flows through, surface water permeating into the aquifer, testing methods. All have an effect on the water’s age. At the bare minimum the results show that the water and aquifer that supply Big Spring are not modern. They are very old and could very well be much older than 1360. So many things factor into how to age the spring that it would take many more tests at different parts of the aquifer to gain a comprehensive insight into the age and size of the aquifer that feeds the spring.

|

| Richard Grayson(left) and Tim Dalbey(right) working to prepare a test site and water sample for the radiocarbon dating test |

The water test was led by archeologist Tim Dalbey. He had floated the idea of the test for over a year and with enough backing and monetary support was able to get the water sample required. Tim does all kinds of interesting things around town. One of the more recent was a mid 19th century cistern discovered by work crews doing renovations of Dealey Plaza in preparation for the 50th anniversary of the JFK assassination. The cistern sits mere feet from the School Book Depository in Downtown Dallas. Byron Harris from Channel 8’s report is below, featuring Tim, the cistern and the assassination:

Current Water Testing Efforts

Tim also ponied up for a water test at Big Spring over a year ago which included a chemical analysis of the water. Those results can be found here June 2012 Water Quality Test At Big Spring

The importance of tests and monitoring is designed to establish a baseline for the future. Starting recently from square one with much of the data collection the avalanche of data regarding the spring and surrounding area now exceeds 5,000 pages of documents and is growing all the time.

The Texas Stream Team, formerly Texas Watch, is based at Texas State University and is affiliated with the university’s River Systems Institute. The team is a partnership of agencies and trained volunteers working together to monitor water quality and educate residents about the natural resources in the state. Established in 1991, the team is administered through a cooperative partnership with Texas State, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The more than 2,000 volunteers are trained to collect water samples according to a water quality plan approved by TCEQ and EPA. The monitors make field observations and analyze the samples for dissolved oxygen, pH, specific conductance, Secchi depth transparency, temperature, and E. coli to assess the quality of aquatic life and contact recreation conditions of the water.

Big Spring has not one but now two data testing sites in conjunction with the Texas Stream Team. Led by Richard Grayson, the DFW coordinator, the two sites labeled:

Meadows Center For Water And The Environment

#80939 Big Spring Source

#80965 Big Spring Pond

Water samples are collected monthly with on site testing for PH, dissolved oxygen. E.coli testing is done offsite at the offices of For The Love Of The Lake.

The City of Dallas has also provided test results of their own at both Big Spring and the Texas Horse Park. Those results can be found at the City of Dallas Stormwater Management website here:

City of Dallas PDF file for water quality at Big Spring and 811 Pemberton Hill Road

Plenty of data exists online to review much of what is going on with Big Spring, the future Texas Horse Park and a future PGA Golf Course. The raw data and documents can most easily be found through a website administered by Hal and Ted Barker here: http://savepembertonsbigspring.wordpress.com/

Hal and Ted were recently featured in a Dallas Observer story about their preservation efforts in Dallas http://www.dallasobserver.com/2013-08-29/news/the-barker-brothers-fight-city-hall-and-win/

|

| Laray Polk crossing Bryan’s Slough at Big Spring hike with city officials |

One recent guest on a hike to Big Spring was author Laray Polk. She has recently written about some of the underlying methane gas issues at the planned PGA Golf Course just a stone’s throw away from Big Spring http://www.dallasnews.com/opinion/north-south-dallas-project/viewpoints/20130811-dallas-world-class-golf-course-must-account-for-methane-threat.ece

The Geology At Work

Big Spring sits in southeast Dallas 32°43’49.06″N 96°43’15.49″W , the neighborhood of Pleasant Grove and the subsection of an area called Pemberton Hill. At roughly 405 feet above sea level, the spring sits in what geologists call the Trinity Terrace.

The Trinity Terrace is a series of orangeish and brown-yellow Pleistocene gravel deposits from a long ago time. The Pleistocene is the geological epoch which lasted from about 2.5 million to 11,000 years ago, spanning the world’s recent period of repeated glaciations. During that time, a vast ice age here in North America, ice sheets and glaciers extended as far south as Kansas. Coupled with much wetter weather than today, the Trinity River was vastly larger, carrying large loads of sediment across a valley that extended from Fair Park clear across to the Dallas Zoo. Big and mighty river, large flood events to boot.

|

| Gravel matrix cemented together by calcium carbonate solution flowing through the rock strata, sample taken from the head source of Big Spring |

The large flood events deposited gravels over the underlying Austin Chalk. The Austin Chalk was deposited roughly 80-90 million years ago during the cretaceous when Dallas was covered in a large sea. In a rare few places you can still see the Trinity Terrace gravel overlying the Austin Chalk.

|

|

| McCommas Bluff Preserve on the Trinity River |

One such place is historic McCommas Bluff, just downstream from the Trinity River Audubon Center. Here one can easily pick out in the northern section of the bluffs, the Trinity Terrace deposits stacked atop the older Austin Chalk.

| Good view of Austin Chalk(white limestone) sitting below the much younger Trinity Terrace gravels(red-brown-yellow gravel matrix) |

Much of the gravel and sand here is loose, one can pick some up barehanded with no effort. In some areas where water has infiltrated over time, the matrix has cemented together. The calcium carbonate solution in the water binds the gravel and sand together forming a hard rock structure.

| Porous water bearing Trinity Terrace gravels cemented together with calcium carbonate and seeping water through the voids, Austin Chalk seen as white rock underneath |

If one looks carefully at the photo above you can see the voids created over time by water slowly moving through the rock at McCommas Bluff.

|

| A natural void or crack in the Austin Chalk that the water has exploited forming a natural seep |

At one particular place along McCommas Bluff a natural seep exists where water exploits a void/flaw/crack/crevice in the limestone. Here the groundwater has created a deep void with crystalline calcium carbonate inside of it. Above is the water bearing Trinity Terrace gravel.

|

| 2009 view of McCommas Bluff Preserve atop the bluffs(bluffs are to the left and out of the photo) |

|

| 2013 view of McCommas Bluff Preserve, same spot as 2009 photo, barren and devoid of vegetation due to 18 wheeler traffic |

The seeps at McCommas Bluff are fragile. Easily impacted by surface activity in the recharge zone beyond. Some seeps have stopped flowing here, others a mere trickle compared to a few years ago. The cause of the degradation was a construction project by Dallas Water Utilities that compacted and ruined much of the land here. Despite assurances that the area was going to be reseeded with new native grass and wildflowers, it never came to pass.

Getting Back To Big Spring

|

| Head source of Big Spring, notice the same gravel matrix visible inside the spring |

|

| Tim Dalbey standing in Big Spring. Visible behind him, to the right is one of the spring’s sources, to the left is a large limestone rock outcrop which serves as an impermeable layer. |

The same geologic structures seen at McCommas Bluff can be seen with a discriminating eye at Big Spring. Looking closely through the vegetation and soil, one can pick out the gravel and limestone boundary inside the spring. Above, Dr Tim Dalbey stands at one source of Big Spring to the right of the photo. To the left and in the background one can pick out the clearly defined limestone vertical face.

More study is required to find out what makes the spring work so well. With such a volume of water one can only wonder what kind of geology focuses so much H2O in one spot.

Loss Of Nearly All Natural Historic Springs

There was a time when Dallas was dotted with springs. Well known in name only, Cedar Springs and Kidd Springs are both great examples of what were once large, functional and important springs in Dallas. There are many more like Keller Springs, Balch Springs and Grapevine Springs that either no longer flow or have been so heavily altered over time that they no longer serve as a touch stone to the past.

There is one place though, one natural spring of importance still out there, that has sat in relative isolation and free from the hands of man. That place is called Big Spring, in the Great Trinity Forest, Dallas, Texas.

Cedar Springs

Across the street from the Whole Foods grocery store in Highland Park stands a modest inscribed stone laid in 1936 to mark the site of Cedar Springs. People know the name. Hundreds of thousands of people drive the road every day bearing the same name. Few have ever seen the actual Cedar Springs or what remains of them not encased in concrete.

|

| Cedar Springs townsite in Dallas Texas, south of Lemmon Avenue and east of the Dallas North Tollroad |

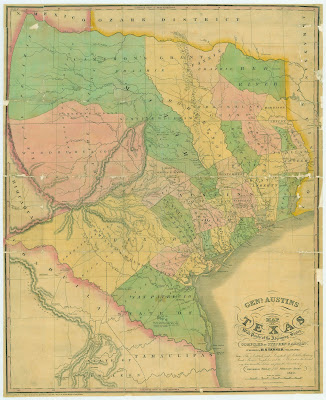

If you could thumb back through that history book and find a year that exemplified a time when the land was fresh in Dallas it would be 1843. Dallas in that year was a vast unpeopled wilderness of plains, known for lush riparian bottoms and a bounty of wild game. The city as we know it today was no more than a dugout scrape of a hovel occupied by one man, John Neely Bryan. Dotting the distant landscape of what was then Nacogdoches County in the Republic of Texas were a scant few homesteads of pioneer families who decided to call what is now Dallas, home. Dallas was not even a going concern at the time. It was Cedar Springs.

Before there was even a Dallas, Cedar Springs served as a small military bivouac for the Republic of Texas. Here Texan military units were reported to camp, exploring and surveying an untamed land that later became DFW. Preston Road was laid out from here. A connection from Holland Coffee’s Trading Post on the Red River at Preston’s Bend with points south towards Austin. Here is where it all happened.

For a time, a serious effort was underway to determine what town should hold the county seat, Dallas or Cedar Springs. The springs were superior to what was offered in Dallas near what is now the Old Red Courthouse. Better land, better water, better living conditions all around. Cedar Springs in it’s heyday boasted a distillery, grist mill, sawmill and a variety of businesses that used the spring for light manufacturing before the Civil War. Those times are long gone, after an election that made Dallas the county seat.

|

| Cedar Springs as it exists today |

At the back end of a city park sits the remains of Cedar Springs. Barely a trickle from it’s source, most likely ruined long ago by a construction project. Bisected by a chain link fence and full of trash, it’s water begins a slow trip under the Dallas North Tollroad.

Under the tollroad in some mix of concrete culverts the water from Cedar Springs mixes with drainages from western portions of Highland Park to form Cedar Springs Branch. Here the flow is a little stronger, just 100 yards distant from the head of Cedar Springs itself.

Under the tollroad in some mix of concrete culverts the water from Cedar Springs mixes with drainages from western portions of Highland Park to form Cedar Springs Branch. Here the flow is a little stronger, just 100 yards distant from the head of Cedar Springs itself.

The west side of the tollroad is where the bulk of the residents lived in what was once Cedar Springs. The waterway is channelized now in a culvert as it passes through a series of gated condo communities and apartment complexes.

Behind one such set of high gates and fences sits a Texas Historical Marker for Cedar Springs. Hard to read from the street(click on the photo to read the inscription). Nothing remains to take stock of today. Long ago gone. Only a street name remains to note the place ever existed.

Kidd Springs

|

| Kidd Springs Park in Oak Cliff |

When Kidd Springs was a going concern, the spring fed lake here was one of the finest swimming holes in the United States. Originally the spring was used by Oak Cliff pioneers in the 1840s-1850s as a water source. When the namesake for the spring Colonel James Kidd purchased the 200 acres of property around the site, he improved upon it. The improvements included turning a natural ravine into a lake via a dam on the northeast and drilling down some distance to improve the flow. The result was a manmade artisanal source up near present day Fouraker Street just north of Davis that ran down to the lake via pipe and then bubbled up into the lake.

|

| A mechanically powered pump simulates the old Kidd Springs outflow using water from the lake |

|

| Kidd Springs rock work that some attribute wrongly as the source |

|

| Yellow Crowned Night Heron among the trash at Kidd Springs |

Kidd Springs at the turn of the last century is where the elite in Dallas spent their summer weekends. A cross between a waterpark and amusement park, Kidd Springs was the place to be seen and put Oak Cliff on the map. Oak Cliff as a community always boasted their clean water as compared to Dallas across the river, Kidd Springs was evidence of that.

Like Cedar Springs, the wheels came off Kidd Springs long ago. Maybe it was the polio scare or the 50’s drought that did the place in. Over time the place just became little more than a memory in the heads of the old timers, people who recalled the elite country club atmosphere of a place long since gone.

Improvements to Kidd Springs Park where the lake now sits incrementally crept away from the lake itself and the park now is as cookie cutter as any other in the city. Concrete sidewalks that replaced the old asian motif decor, the rock work replaced by more functional but bland access for ADA compliance.

Big Spring

Seventeen decades, a whole 170 years of documented Texas history lie here. In a chronological history book of Dallas history, the intertwined lore of this spot would be written on page one.

|

| The evening sun setting behind Big Spring |

Around the time Cedar Springs was founded, a year or two after John Neely Bryan started calling his dugout hole near what as now the Old Red Courthouse, a family called the Beemans settled in North Texas on lower White Rock Creek.

Around the time Cedar Springs was founded, a year or two after John Neely Bryan started calling his dugout hole near what as now the Old Red Courthouse, a family called the Beemans settled in North Texas on lower White Rock Creek.

Veterans of the Republic of Texas Army and Indian campaigns, the Beemans by the early 1840s had already made their mark on the infant Republic’s history. They settled on White Rock Creek on land claims given to them by the Republic of Texas for military service and land purchased via Toby Script. One parcel of land was known as the “Big Spring Survey”, claimed in 1842 by John Beeman in what was then the Peter’s Colony Survey. John Beeman and his family lived on the west bank of White Rock Creek just down the hill from the present day Beeman Family Cemetery.

|

| Big Spring as it looked on the evening of August 13, 2013, 170 years to the date that President Sam Houston camped here |

John Beeman called this piece of land “Big Spring” after the cold and clear water that flows straight off the bedrock via a natural spring. Used for countless centuries by Native Americans, this site had been a magnet for humans seeking water and refuge. Even present day the water still flows at a near consistent 60 degrees. Who knows what kind of people once drank from the water here. What language they spoke. What they ate for dinner.

Sam Houston and his Treaty Party visit Dallas and a high probability that they camped one night at Big Spring

|

| Sam Houston |

Sam Houston had lived with the Cherokee people for years as a young man, had a fondness for the tribes and wanted them treated fairly as their lands were taken over by civilization despite their depredations against the settlers in Texas. For months Houston sent messages to his Indian friends proclaiming he would hold a Grand Council of the Tribes at Fort Bird(presently in the North Arlington area) during the full moon of August 1843. Similar to what we might consider a general assembly meeting of the United Nations. Houston sent Indian Commissioner Joseph C. Eldridge out months in advance of the date to bring the Comanches and others to the treaty council.

It was in August 1843 when Sam Houston and an expedition of about 30 men departed Crockett in East Texas, and began their trek to the Three Forks of the Trinity(now known as Dallas and Tarrant County) to negotiate with the chiefs of the Indian tribes. Their route was well documented traveling roughly on the same route into Dallas that US Highway 175 takes today. This route was an ancient Pre-Columbian trail used by Indians for many centuries as an important trade route between the Piney Woods of East Texas, the Plains and Indians living north of the Red River. Scyene and Preston Roads share similar distinctions in Dallas as ancient Indian trails that later became major roads.

|

| Big Spring Sunset among the native walnut and pecan trees |

One of the men in his group was an Englishman by the name of Edward Parkinson. He kept a detailed account of the trip in his diary. It’s believed he came along just for the adventure of seeing real live Indians on the plains. At the time the Beeman family was living in a blockhouse near present day Dolphin Road and Military Parkway. The account below mentions that they did not see the Beeman family until the next morning, August 14th 1843. His diary entries from August 13th and 14th or there abouts follow…..

“We encamped that night at White Rock Springs, so called from the calcareous nature of the rocks abundant here about one mile from the White Rock Fork of the Trinity. In the morning some settlers from the infant colony opened about the Forks of the Trinity River visited us, accompanied by some travelers examining the country, they brought us no news of the expected Indians and were on foot, stating that some little time previous the wild Indians had stolen all the horses but one or two belonging to the settlement. We then saddled up and proceeded to the fork at White Rock Creek which we found very difficult from the rain which had fallen making the bank on the other side one slide of about thirty feet, from top to bottom. We were obliged to dismount and drive the animals over, some of them describing curious mathematical figures, from their inexperience in the science of sliding. However, all got over safe, and on reaching the prairie on the other side arrived at one of the colonist’s cabins{that of John Beeman} where we were regaled with an acceptable and plentiful supply of buttermilk. My horse(a mustang) having become almost knocked up, I determined upon resting here, and was hospitably entertained until the following day, the company in the meantime moving on to Cedar Springs, where they rested a day or two previous to marching on to Bird’s Fort on the West Fork of the Trinity the appointed Treaty Ground, great anxiety prevailing respecting the Indians but no news of them.”–Edward Parkinson 1843

|

| Sam Houston |

When Houston arrived at Ft. Bird, several tribes had shown up but did not want to go near the garrisoned fort fearing a trap. Houston moved the negotiations and camps six miles north to Grapevine Springs. He felt the Springs offered better water, more shade in the summer heat and less mosquitoes. However the group camped there for more than a month while awaiting the Comanches, and was described by Parkinson as: “there were some fine though rather monotonous days, only relieved by finding a bee tree or killing our beeves.” Finally Houston realized the Comanches weren’t coming and decided to have a council with those in attendance. Known as a flamboyant dresser, Houston’s attire for the occasion was noteworthy. “Donned in a purple velvet suit, with a huge Bowie knife thrust in his belt, and a folded Indian blanket draped over one shoulder to proclaim his brotherhood with the red men, Houston eloquently promised the chiefs that a favorable treaty line would be drawn beyond which the Indians could live unmolested by white men.” At this time, along with the negotiations with the Indians, Houston was still President of the Republic and having to deal with the Mexican situation and annexation of Texas. Before the actual treaty was signed, he had to go back to Washington on the Brazos to deal with these issues personally. To deal with the Comanches when, and if, they arrived he assigned Gen. Edward H. Tarrant and Gen. George Whitfield Terrell.

|

| Treaty of Bird’s Fort |

The treaty was signed in the last three days of September 1843. The Treaty at Birds Fort was a rare instrument: it was actually ratified by the Republic of Texas Senate. Throughout both his administrations, Sam Houston worked to negotiate with the Texas tribes, not only because of his natural inclination but also because the new Republic simply could not afford to be at war both with the Indians and the Mexicans. His policy had already been put into practice when he and John Forbes negotiated a treaty with the Cherokee on February 3, 1836. President Mirabeau B. Lamar, on the other hand, was convinced that the tribes were conspiring with the Mexicans, and he also believed that the tribes constituted a foreign nation in competition with the Republic. He actively supported a policy of extermination and expulsion, a policy which removed the Cherokee altogether and which helped plunge the new nation into considerable debt.

Native Americans

Springs in Texas have been a magnet for human activity for many dozens of centuries. Find an undisturbed spring site almost anywhere in the Lone Star State and one will readily find evidence of human occupation that goes back thousands of years. The old watering holes of the first Americans later became well worn routes of travel that were used by the first European expeditions to Texas. Those old game trails and hunting routes eventually morphed into wagon roads, some became modern day highways we know today.

|

| Native American artifacts excavated from 41DL72 as part of a Geo-Marine project in 2013. Photo Credit: Tim Dalbey |

A wide swath of an archeological site once covered the terrace upon which Big Spring sits. Over the last hundred years, through utility right of ways, easements and some gravel mining, the site, officially called 41DL72 slowly diminished in size. Remnants of the site still exist undisturbed. The effort to save the remaining undisturbed area for the future is a tough sell.

|

| One oddball layered map that literally looks like a footprint from Geo-Marine |

|

| Measuring DL72 in the electric ROW |

For an area that looks so quiet, so untouched, the complexity of issues facing the place can best be described in the map above. What are 6 maps laid over one another show all the competing projects and eyes on design for the place. Some ideas, like the fencing of the spring are now just a distant memory. Others are still a concern as bulldozers begin work on the Texas Horse Park.

The work to map some of the areas has consumed many an early Saturday morning this summer. Measuring, driving stakes, measuring again, taking copious field notes and photos. All to preserve a place that links some ancient people to us. I don’t even know who they are. No one does. If the bulldozers don’t wreck it maybe one day we will find out.

|

| Mapping out a DL72 protection area |

| Runaway horses bathing in Big Spring 2012 |

Protecting the spring and the surrounding area is vitally important to the health and long term sustainability of Big Spring and the Native American site around it. “Protecting” and “protection” of a place can mean many things to many people. How one comes to consensus on what is best to protect one of the last natural springs in Texas, how we all figure that out is a tough one. Lots of big, gigantic promises being made. Hope it’s not all talk.

|

| The large field above Big Spring which serves as a bio-buffer for the spring |

|

| Another view of the field, standing NE corner, looking SW, Texas Horse Park will sit beyond the transmission lines |

|

| The idea that never was |

According to the City of Dallas, hired consultants for a time floated the idea of equipment buildings, two 1,000 gallon fuel tanks and a compost heap that would have commanded most of the land in the field here. See inset left. Those plans according to the City of Dallas were only ideas and never a serious consideration.

Talks with the city thus far in reaching preservation and conservation status have been productive and are seeing much progress. A large buffer is the right solution to the perpetual preservation of the Big Spring site, the preservation of the Native American site and leaving the woods surrounding the Spring free of anything but foot traffic. It should be a place that is open and enjoyed by all who want to visit. With discussion for a detailed and comprehensive management plan, conservation and preservation it’s thought that the sights and sounds seen today will look the same 500 years from now. There is an abundant and rich reward for leaving places like this alone.